Text: United States of America: Government 101. A brief overview and case study. Image shows an American flag with a dark blue banner with the text.

Understanding the Levels of Government in the United States

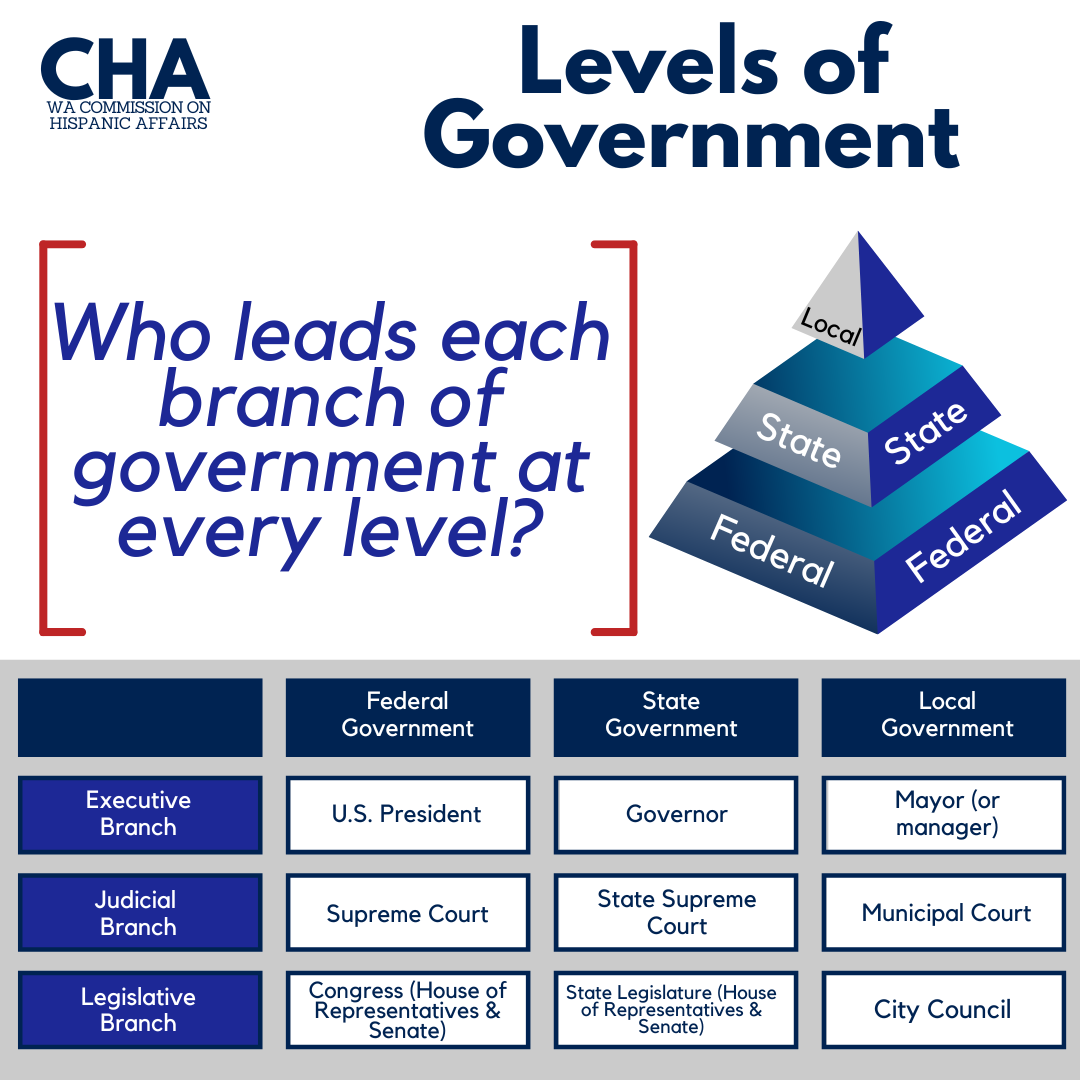

As our country and state navigates changing administrations, CHA is launching a series to dive deeper into the levels of government. The United States government operates at three primary levels: federal, state, and local. Each level has its own responsibilities, powers, and officials who work together to govern effectively as outlined in the Constitution. Federal, state, and local governments all have an Executive Branch, Legislative Branch, and Judicial Branch to maintain separation of powers. Learn more about the Separation of Powers and Checks and Balances.

Scope of Authority

Each level of government operates independently but also collaborates to serve the public. Federal laws take precedence over state and local laws, meaning that state and local governments must comply with national regulations. However, states have the power to create and enforce their own laws in areas not explicitly covered by federal law. Local governments (county and municipal) operate under state authority and handle community-specific needs like zoning, public safety, and sanitation. While cities and counties must follow state laws, they have autonomy in managing local services and regulations. Special districts operate within counties and cities to provide specific services, often in partnership with state and local agencies.

Federal Government: The federal government is the highest level of authority in the United States and is responsible for governing the entire country. It oversees national policies related to defense, foreign relations, interstate commerce, and constitutional rights. The federal government is divided into three branches: the executive branch, led by the President, which enforces laws; the legislative branch, consisting of Congress (Senate and House of Representatives), which creates laws; and the judicial branch, which includes the Supreme Court and lower courts that interpret and uphold the law.

-

The power of the Executive Branch is vested in the President of the United States, who also acts as head of state and Commander-in-Chief of the armed forces. The President is responsible for implementing and enforcing the laws written by Congress and, to that end, appoints the heads of the federal agencies, including the Cabinet. The Vice President is also part of the Executive Branch, ready to assume the Presidency should the need arise.

The Cabinet and independent federal agencies are responsible for the day-to-day enforcement and administration of federal laws. These departments and agencies have missions and responsibilities as widely divergent as those of the Department of Defense and the Environmental Protection Agency, the Social Security Administration and the Securities and Exchange Commission.

Including members of the armed forces, the Executive Branch employs more than 4 million Americans.

-

Established by Article I of the Constitution, the Legislative Branch consists of the House of Representatives and the Senate, which together form the United States Congress. The Constitution grants Congress the sole authority to enact legislation and declare war, the right to confirm or reject many Presidential appointments, and substantial investigative powers.

The House of Representatives is made up of 435 elected members, divided among the 50 states in proportion to their total population. In addition, there are 6 non-voting members, representing the District of Columbia, the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico, and four other territories of the United States. The presiding officer of the chamber is the Speaker of the House, elected by the Representatives. He or she is third in the line of succession to the Presidency.

Members of the House are elected every two years and must be 25 years of age, a U.S. citizen for at least seven years, and a resident of the state (but not necessarily the district) they represent.

The House has several powers assigned exclusively to it, including the power to initiate revenue bills, impeach federal officials, and elect the President in the case of an electoral college tie.

The Senate is composed of 100 Senators, 2 for each state. Until the ratification of the 17th Amendment in 1913, Senators were chosen by state legislatures, not by popular vote. Since then, they have been elected to six-year terms by the people of each state. Senator's terms are staggered so that about one-third of the Senate is up for reelection every two years. Senators must be 30 years of age, U.S. citizens for at least nine years, and residents of the state they represent.

The Vice President of the United States serves as President of the Senate and may cast the decisive vote in the event of a tie in the Senate.

The Senate has the sole power to confirm those of the President's appointments that require consent, and to ratify treaties. There are, however, two exceptions to this rule: the House must also approve appointments to the Vice Presidency and any treaty that involves foreign trade. The Senate also tries impeachment cases for federal officials referred to it by the House.

In order to pass legislation and send it to the President for his signature, both the House and the Senate must pass the same bill by majority vote. If the President vetoes a bill, they may override his veto by passing the bill again in each chamber with at least two-thirds of each body voting in favor.

-

Where the Executive and Legislative branches are elected by the people, members of the Judicial Branch are appointed by the President and confirmed by the Senate.

Article III of the Constitution, which establishes the Judicial Branch, leaves Congress significant discretion to determine the shape and structure of the federal judiciary. Even the number of Supreme Court Justices is left to Congress — at times there have been as few as six, while the current number (nine, with one Chief Justice and eight Associate Justices) has only been in place since 1869. The Constitution also grants Congress the power to establish courts inferior to the Supreme Court, and to that end Congress has established the United States district courts, which try most federal cases, and 13 United States courts of appeals, which review appealed district court cases.

Federal judges can only be removed through impeachment by the House of Representatives and conviction in the Senate. Judges and justices serve no fixed term — they serve until their death, retirement, or conviction by the Senate. By design, this insulates them from the temporary passions of the public, and allows them to apply the law with only justice in mind, and not electoral or political concerns.

Generally, Congress determines the jurisdiction of the federal courts. In some cases, however — such as in the example of a dispute between two or more U.S. states — the Constitution grants the Supreme Court original jurisdiction, an authority that cannot be stripped by Congress.

The courts only try actual cases and controversies — a party must show that it has been harmed in order to bring suit in court. This means that the courts do not issue advisory opinions on the constitutionality of laws or the legality of actions if the ruling would have no practical effect. Cases brought before the judiciary typically proceed from district court to appellate court and may even end at the Supreme Court, although the Supreme Court hears comparatively few cases each year.

Federal courts enjoy the sole power to interpret the law, determine the constitutionality of the law, and apply it to individual cases. The courts, like Congress, can compel the production of evidence and testimony through the use of a subpoena. The inferior courts are constrained by the decisions of the Supreme Court — once the Supreme Court interprets a law, inferior courts must apply the Supreme Court's interpretation to the facts of a particular case.

State Government: Each of the 50 states has its own government that operates independently within its jurisdiction. State governments manage a range of responsibilities that directly impact residents, such as education, transportation, healthcare, and state law enforcement.

Washington State Government: Washington State’s government operates under a system similar to the U.S. federal government, with three branches—executive, legislative, and judicial—that balance power and work together to serve residents. The state constitution outlines the structure, rights, and responsibilities of state leaders and institutions. Washington also includes local governments (counties, cities, tribes, school boards, and special districts), each with its own authority to address community needs. Residents can propose or vote on laws directly through ballot measures.

Image of Washington’s 49 legislative districts

-

Led by: Governor (currently Bob Ferguson as of 2025)

Role: Enforces state laws and oversees executive agencies

Includes:

Lieutenant Governor, Attorney General, Secretary of State, State Treasurer, State Auditor, and other elected officials

Over 100 state agencies, boards, and commissions (e.g., Department of Health, Department of Ecology, Department of Transportation)

-

Body: Washington State Legislature

Role: Creates state laws, passes budgets, and represents the people

Structure:

Senate – 49 Senators (one per legislative district)

House of Representatives – 98 Representatives (two per district)

Meets: Annually in Olympia during the legislative session (January–April or longer in odd-numbered years)

-

Role: Interprets state laws and ensures justice is upheld

Includes:

Washington State Supreme Court (highest court)

Court of Appeals

Superior Courts, District Courts, and Municipal Courts

Judges are elected by voters (not appointed)

Local Government: Local governments operate at the county, city, or town level and handle the day-to-day affairs of communities. They manage services like public schools, law enforcement, zoning regulations, sanitation, and transportation. Local governments are structured to meet the needs of their specific populations and are typically divided into county governments, which oversee regional services, and municipal governments, which focus on city-specific operations. Local officials, such as mayors, city councils, and commissioners, are responsible for ensuring community needs are met efficiently.

Washington Local Governments: Washington has 39 counties and hundreds of cities, towns, and special purpose districts. These local governments manage public safety, zoning and land use, utilities and transportation, local elections and records, and community services like libraries, parks, and public health. Local officials include county commissioners, mayors, city council members, sheriffs, and school board members—most are elected directly by the public.

-

Mayor (in mayor-council systems)

Elected by voters

Oversees city departments, budgets, and daily operations

May have veto power over city council decisions

City or County Manager (in council-manager systems)

Appointed by the city council

Acts as chief administrator

Manages departments, staff, and policy implementation

Elected Executives in Counties

Examples: County Executive, Sheriff, Assessor, Auditor, Treasurer

Each handles specific functions like public safety, elections, and records

-

City Council / Town Council / County Council or Board of Commissioners

Elected by district or at-large

Pass ordinances (local laws), adopt budgets, set policy direction

Represent community interests and hold public hearings

In counties, the Board of County Commissioners or County Council acts as the legislative body

-

Municipal Courts (in cities and towns)

Handle traffic violations, misdemeanors, and city ordinance cases

District Courts (at the county level)

Handle civil cases, traffic infractions, and criminal misdemeanors

Superior Courts (county-level, but part of the state system)

Handle felonies, family law, juvenile cases, and civil suits over $100,000

Tribal Sovereignty in Washington State

Washington is home to 29 federally recognized tribes, each with its own sovereign government. Tribal sovereignty means that these nations have the inherent right to govern themselves, manage their lands, enforce laws, and protect the wellbeing of their people—independent of state or local governments.

-

Tribal governments have their own constitutions, elected leaders (such as Tribal Councils), and justice systems. They oversee vital areas like education, healthcare, housing, environmental protection, and cultural preservation. Many also operate enterprises such as casinos, fisheries, or natural resource programs that support their communities and economies.

The relationship between tribes and the U.S. government is based on treaties, federal law, and court decisions—not granted by the state. Tribes are not subordinate to Washington State; they are separate, self-governing nations that interact with federal and state governments on a government-to-government basis.

Washington State has a strong history of tribal advocacy and leadership, and many agencies and departments now work in formal partnership with tribes to coordinate policies and services. This includes areas like environmental stewardship, public health, crisis response, education, and emergency management.

Recognizing and respecting tribal sovereignty is not only a legal responsibility—it’s a key part of honoring Indigenous history, culture, and leadership in Washington.